Memento Park, located on the outskirts of Budapest, is a space dedicated to preserving statues and symbols of Hungary’s communist period. Far from being a traditional park, this place offers a direct look at the country’s recent past, through monuments that once occupied public spaces during the socialist regime. Visiting it is a unique experience: a tour among sculptures of leaders, soldiers and workers that, beyond their artistic value, represent a key period in Hungarian history.

The first impact

As soon as you arrive at the park, you don’t find an ostentatious entrance like that of the Museum of Fine Arts or the Hungarian National Museum, but a brick wall that already conveys a sense of serenity. Right at the entrance, as if waiting for us, are the statues of Karl Marx and Lenin.

The three gates through which you enter the park already allow you to see some of the statues, as if they had nothing to hide. I found this rather curious, because in most museums I have visited it is not possible to see the contents until you enter. When you get to the entrance, behind you stand Lenin’s huge boots, placed on a large pedestal that you can climb on. I really felt like I was at his feet; it was a curious sensation.

Once inside, you find a small picnic area made of wooden pallets, an old car and a telephone booth (which I didn’t actually try to see if it worked). There is also a small souvenir shop, where you can buy tickets. Unlike other museums, there was no extra security: there was only the lady at the entrance – very friendly and lively, by the way – charging visitors with all the good faith in the world.

As soon as I arrived, she recommended a booklet with a small guide to the park and what we were going to find. The truth is that, with the effusiveness with which he explained it, I felt like buying it… and I wasn’t wrong. It’s totally recommendable: for 2000 HUF (about 5 €), you get to know all the monuments in the park very well.

A walk through history

Memento Park is divided into two distinct but complementary spaces: the Statue Park and Witness Square. This division is not only physical; it also marks two distinct ways of approaching Hungary’s communist past: one more monumental and the other more introspective.

My visit began in Statue Park, the main and most striking area. Seen from above, the paths in this area are shaped like lying eights, like symbols of infinity. Thus, the walks seem to turn in on themselves, infinite, leading nowhere except to the central path, which imposes itself as the only one, the true one, the right one. This layout conveyed to me how the people of the time must have felt: everyone following the marked route, the one that was supposed to work, but which in the end leads to a wall. Two iconic statues stand there: Captain Steinmetz and Ostapenko, who once greeted and dismissed citizens on the outskirts of Budapest. Now, reunited in this park, they bid farewell to visitors after this dead end. A truly representative image.

This is where the great sculptures that once occupied Budapest’s squares, avenues and official buildings can be found. Seeing them gathered together in a relatively small space is striking: huge figures of Lenin, Karl Marx, Béla Kun, Red Army soldiers and anonymous workers parade in stone and bronze, as if still representing a discourse that no longer has an audience. Most are set on brick bases, which reinforces the sense of solemnity. Walking among them is like walking through a frozen, ideologically charged scenography, which no longer has a place in the present, but which has not been forgotten either.

After exploring this area, I moved on to Witness Square, a lesser-known but equally powerful part of the park. Here, in a smaller and more secluded indoor space, a documentary film entitled The Life of an Agent is shown. The short film shows real images and testimonies about how the system of state surveillance and control functioned during the communist regime: telephone tapping, surveillance, secret files, informers…. Everything that seemed distant or abstract becomes much more tangible.

I remember sitting in the auditorium with no great expectations, but I ended up watching the whole documentary. I was struck by the coldness with which the methods of internal espionage were described, and how many of the agents seemed neither remorseful nor particularly aware of the damage they had caused. It was a kind of necessary counterpoint to the epic discourse of Statue Park: if power and propaganda are shown there, here the everyday fear, surveillance and manipulation of private life is revealed.

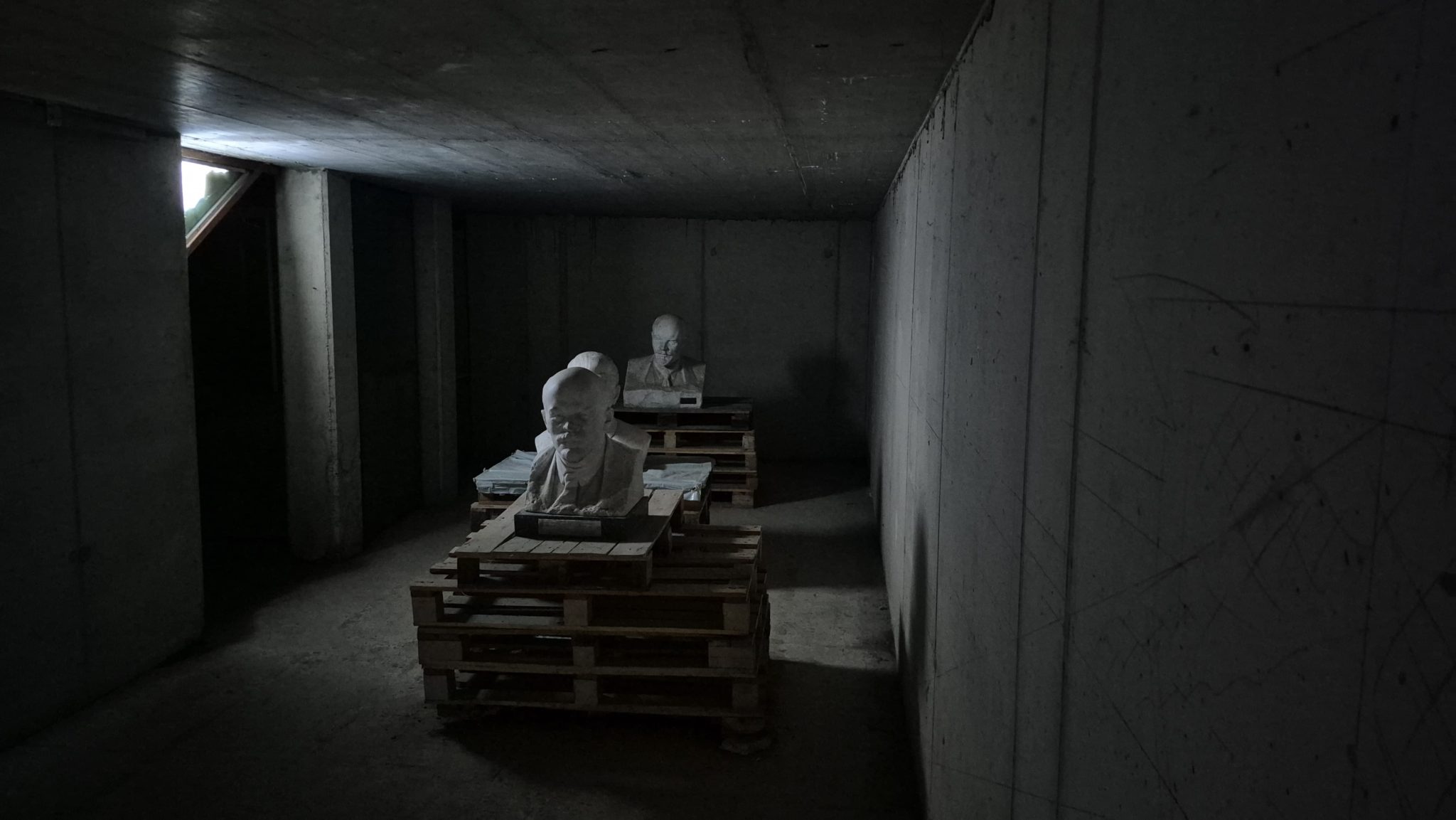

Then I went to the statue of Stalin, where one can climb up and look down on the park from a higher altitude. There are also good views of the city in the distance. But the most interesting thing was to go down into the underground space below. There I came across several busts and statues of Soviet leaders. What struck me most was the atmosphere: a lonely, bare concrete space, with no lights other than the one coming through the open door and a spotlight illuminating a particular figure. There was a stool where the visitor seemed to be invited to sit and observe this cold and silent scene. The smell of dust and the gloom gave me a strange sense of tranquillity. The statues were there, immobile, with lost but confident gazes, as if they were affirming that everything was going to be all right… although the dark atmosphere took away their strength. I would say it was the part I liked the most: alone, in silence, accompanied by statues that seemed to speak without saying anything.

As I left Witness Square, I felt I had come full circle. It was no longer just a walk among ancient sculptures: it had been a more complete experience, which helped me to better understand what it was like to live under a regime where everything was controlled and everything had a message.

Personal reflections

Memento Park seems to me to be an excellent way of remembering the past. In the end, we learn from everything, and erasing history does not help to avoid repeating it; quite the opposite. Historical memory is fundamental to understand where we come from, how our societies have been built and what mistakes we should not make again.

During authoritarian regimes, one of the first steps towards control was to eliminate critical thinking: burning books, banning ideas, erasing faces from photographs or tearing down statues that did not conform to the official discourse. I find it worrying that today, in the name of justice or political correctness, the same symbolic gestures of destruction are repeated. I believe that no matter the ideology, the era or the political system, no one should have the power to decide which part of the past deserves to be remembered and which does not.

What I liked most about the park, located on the outskirts of Budapest, is precisely this desire to show rather than hide. Rather than being a space that seeks to hide an uncomfortable period, it is a place that invites us to teach and reflect on what communist Hungary once was: how it was lived, what symbols were used and how the regime finally fell. It is a park that does not glorify, but neither does it erase. The statues are no longer there to celebrate, but to make people think. Their value lies precisely in this change of function: they have gone from being symbols of power to become educational tools.

In Spain, my native country, we are also burdened with a painful past. The Franco dictatorship that began after the Civil War in 1939 and ended with Franco’s death in 1975 left deep traces. But what worries me most is not so much that we have that history, but that it has become a political weapon. Today, monuments, archives, streets and references to everything related to that period are censored, destroyed or ignored. I am not saying that it was a good time for Spain, nor that it should be celebrated, but I do firmly believe that it is dangerous to try to erase the past instead of confronting it with maturity.

History must not be rewritten or simplified; it must be known, understood and debated. Only in this way can we build a freer and fairer society, without repeating the mistakes that once led us to disaster.

I find it incredible that here in Budapest I have found more references to the Spanish Civil War than in my own country. The monument to the soldiers of the International Brigades was the first tribute I have seen dedicated to that conflict, even though it took place in Spain and its consequences are still felt today. In my city, Seville, one of the first to fall under Franco’s regime, hardly any traces of that era remain: little by little they have been removed and hidden, as if erasing the symbols could erase what happened. But history does not disappear so easily.

Karl Marx wrote that ‘history happens twice: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce’. I sometimes wonder whether, by insisting on forgetting rather than learning, we are not leaving the door open for certain mistakes to return in other forms.

Comments are closed.