The Millennium Underground line, known in Hungarian as ‘Kisföldalatti’ (literally ‘the little underground’), represents a major milestone in the history of urban transport not only in Hungary, but in Europe as a whole. Inaugurated on 2 May 1896, in commemoration of the 1,000th anniversary of the arrival of the Magyars in the Carpathian Basin, this line became the first electric metro on the European continent, surpassing similar systems in cities such as Paris (1900) and Berlin (1902).

Built in record time and with a clear forward-looking vision, the Millennium Underground was not only a technical achievement, but also a statement of modernity by Budapest, which at the time was part of the burgeoning Austro-Hungarian Empire. The line was designed to improve the connection between the city centre and the City Park (Városliget), facilitating access to the millennium celebrations and the exhibition grounds.

Unlike later subways, this line was built just below Andrássy Avenue, at a superficial level, making it an early example of respect for the urban environment and architectural heritage. Its elegant and functional infrastructure has been recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2002, along with Andrássy Avenue itself.

Historical context

The construction of the M1 line in Budapest was part of Hungary’s millennium celebrations in 1896, commemorating the thousand years since the arrival of the Magyar peoples in the Carpathian Basin. This great event was not only a national celebration, but also an opportunity to showcase the country’s progress and modernity within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to which Hungary belonged at the time. Budapest, which was undergoing a period of rapid expansion and urban transformation, was positioning itself as a booming European capital, comparable to Vienna or Paris.

The metro was conceived to facilitate the transport of visitors from the city centre, at Vörösmarty Square (then Gizella tér), to the City Park (Városliget), where the main festivities and exhibitions of the millennium were concentrated. In order to preserve the aesthetics of the newly built and prestigious Andrássy Avenue, the authorities decided that the railway should go underground, avoiding the alteration of the urban landscape above ground.

Although the Hungarian Parliament approved the project in 1870, construction did not begin until 1894. In just 21 months, the German company Siemens & Halske AG, with a team of more than 2,000 workers, completed the line using the innovative cut-and-cover method, which allowed the tunnel to be excavated, constructed and closed quickly without unduly disturbing the environment.

The original 3.7-kilometre line had 11 stations – nine underground and two above ground – and carried some 35,000 passengers a day from its first year. Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary officially inaugurated the service on 2 May 1896, and after travelling on it on 8 May, authorised it to bear his name, and it became known as the Franz Joseph Underground Railway (Franz Joseph Untergrundbahn). The system was an immediate success, with trains running every two minutes, and marked the beginning of modern metropolitan transport in continental Europe.

Technological innovation

The Millennium Underground line was not only pioneering as the first electric metro on the European continent, but also represented an unprecedented technological feat of its time. Unlike the London Underground, which opened in 1863 with trains powered by steam locomotives – which generated large amounts of smoke and heat in the closed tunnels – the M1 line in Budapest opted from the start for all-electric traction, which improved the healthiness, efficiency and safety of the system.

The electrification system was designed with a 550 volt direct current (DC) overhead power supply, a novel and complex solution for the late 19th century. The current was supplied through overhead contact lines, as the confined space of the tunnels made the use of a third rail, common in other later systems, unfeasible. This technical choice made it possible to operate low profile trains, ideal for the shallow tunnel built by the cut and cover method.

The original 20 carriages were manufactured by the Siemens & Halske company, and reflected both technical innovation and attention to aesthetic detail. Some units were built in wood, others in metal, and one of them was specially fitted out for Emperor Franz Joseph, with luxury finishes. Despite their small size, the trains could reach a maximum speed of 27.4 km/h, more than enough to cover the 3.7 km line quickly and safely.

The overall design of the line was overseen by Hungarian engineer Mór Balázs, who received a noble title in recognition of his outstanding work on this national project. The construction faced significant technical challenges, such as interference with the sewerage system at the junction with the Grand Boulevard (Nagykörút), but these were effectively resolved without major delays, thanks to rigorous planning and the expertise of the construction team.

In addition to functionality, the project paid special attention to urban and artistic design. The station signs were manufactured by the renowned Zsolnay Porcelain Factory in Pécs, famous for its high-quality enamelled ceramics, while the metro entrances, some of which remain to this day, were designed by Albert Schickedanz, the same architect responsible for the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. Its Art Nouveau style and its harmony with Andrássy Avenue reflected a desire to integrate modern technology with the elegant urban environment of the Hungarian capital.

Architectural and cultural significance

The M1 line is more than a means of transport; it is a testimony to the urban and cultural development of Budapest in the late 19th century. In 2002, Andrássy Avenue, together with the Millennium Underground line, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognising its historical and architectural importance. The stations, decorated with Zsolnay tiles, reflect the style of the period, while the original entrances, although some were demolished after World War I, were outstanding examples of Art Nouveau.

The Underground Museum, located in Deák Ferenc Square, offers an immersive experience of the line’s history. Open since 1975 in a 60-metre tunnel section abandoned in 1955, the museum exhibits three historic carriages (numbers 19, 1 and 81), original documents, photographs and models. Highlights include a marble plaque commemorating Franz Joseph’s visit in 1896 and the original ‘Gizella tér’ inscription with Zsolnay tiles.

The line has also served as a stage for cultural initiatives. For example, in November 2022, the Budapest Transport Company (BKV) organised an event in which artists recited poems at the stations during the Advent season, demonstrating that the M1 is still a living and relevant space.

Developments and current status

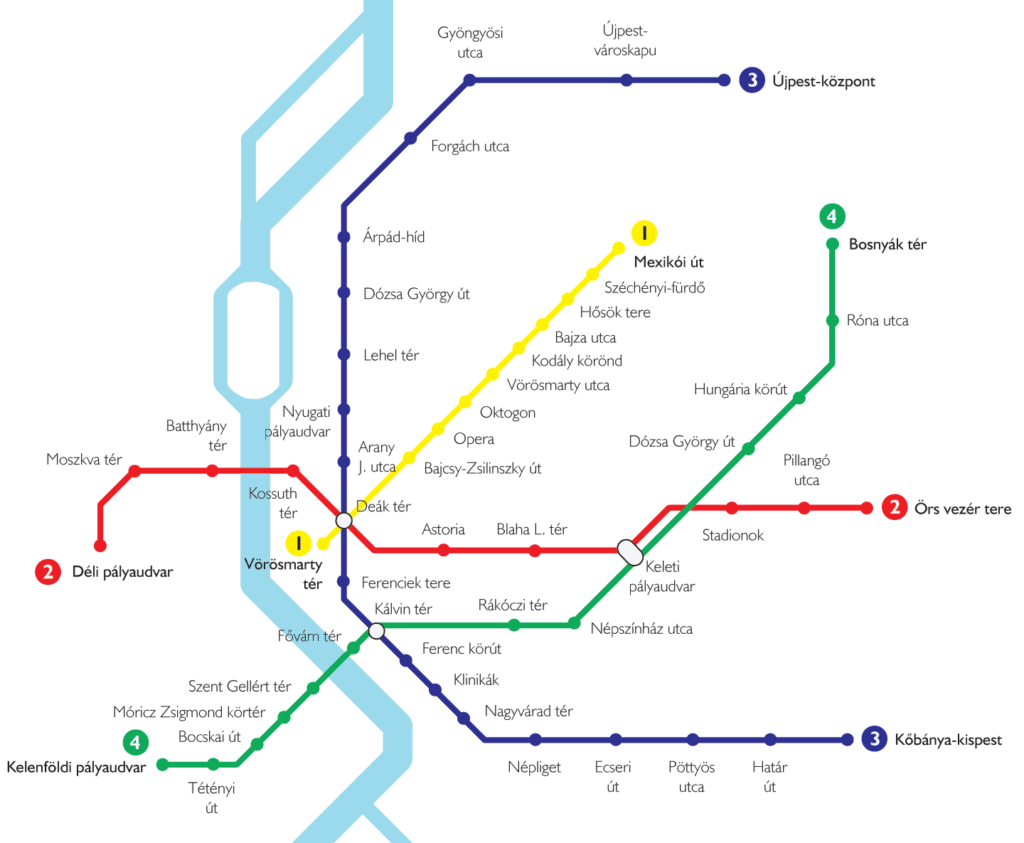

Since its opening, the M1 line has undergone several modifications. In the 1950s, an 80-metre section was abandoned to make way for the construction of the M2 line. Between 1970 and 1973, the line was extended to Mexikói út, eliminating the surface section through the City Park and adopting right-hand traffic instead of the previously used left-hand system. In 1995, renovations were carried out due to wear and tear of the infrastructure.

Today, the M1 line, with a length of 4.4 km and 11 stations, carries about 80,000 passengers daily. The current Ganz MFAV carriages, introduced in 1971, are obsolete, having exceeded their 40-year service life. By 2025, BKV estimates that replacing the 22 trains needed will cost HUF 45.4 billion (approximately 113.8 million euros), including planning costs and maintenance equipment. However, financing is an obstacle, and BKV has received permission to apply for a loan from the European Investment Bank if public funds are not forthcoming.

Despite these challenges, there are plans to extend the line to Rákosrendező as part of the ‘Millennium City Center’ or ‘Maxi-Dubai’ project, which would include new residential, commercial and park developments. These initiatives reflect Budapest’s commitment to the preservation and modernisation of this historic icon.

Comments are closed.